What’s the buzz on “biogas”—an alleged renewable energy source that comes from dairy farming? Dairy comes with several dilemmas these days, not the least of which is its environmental impact.

With Shavu’ot approaching–a Jewish holiday widely known for its dairy food traditions–JIFA interviewed Trevor McCarty, Policy Manager at Farm Forward, about the use of biogas digesters in dairy farming and why consumers and communities should care about their expansion.

Can you talk about the scale and impact of dairy farming operations in the United States—how many animals are on farms?

Paradoxically, over the past 30 years the number of dairy farms has gone down, yet milk production has gone up. This is because the industry is rapidly consolidating and running smaller operations out of town, since economies of scale allow for large dairies to operate more efficiently than smaller-scale ones. Modern dairy cows have also been genetically selected for high milk production, and technological changes have contributed to that increase as well. From 2017 to 2022, the number of dairy farms in the U.S. contracted from 39,303 to 24,082.

The majority of milk produced in the U.S. comes from farms with over 1,000 cows, where the largest dairy operations may have over 15,000 cows in total (AKA a mega-dairy, and a form of confined animal feeding operation, or CAFO). As of 2017, over 50% of dairy cows lived on farm operations with over 1,000 animals, and in February 2024, the total U.S. dairy cow herd was estimated to consist of 9.33 million cows.

Recently, several reports have come out on the use of ‘biogas’ as an energy source which comes from farms, including dairies.

What is biogas and why is biogas being called “renewable”? Where could the money being used on their development go instead?

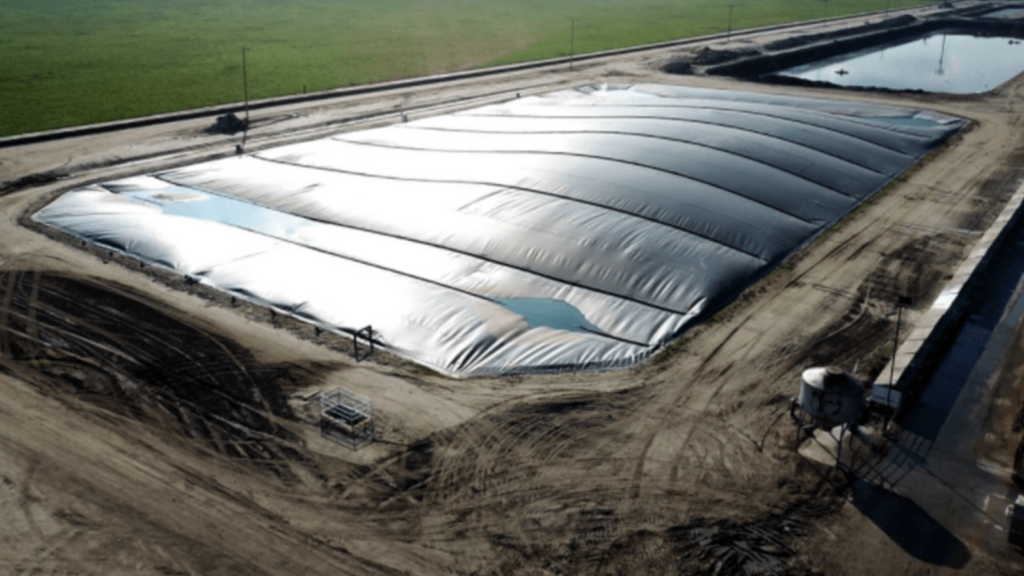

Manure biogas—that is, the mix of gasses, primarily methane, that comes from dairy manure lagoons—is produced from the decomposition of organic matter, primarily animal waste under anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions. The process, known as anaerobic digestion, utilizes microorganisms to break down this material, resulting in the production of methane and other gasses. This collection of gas can be used more or less identically to how traditional natural gas is used: heating, electricity generation, and can even be developed into transportation fuel. Anaerobic digesters can be installed to collect the gas.

Biogas is sometimes referred to as “Renewable Natural Gas” or RNG. This is to distinguish it from fossil fuel-based natural gas that comes from hydraulic fracturing, AKA fracking, which has a clear limit to its supply. Since biogas is made from organic matter which can be replenished, it is often classified as “renewable.” However, biogas is not renewable in the way sunlight and wind are; its vast availability isn’t naturally occurring in nature.

Instead, it relies on the continuation of intensive livestock farming—dairy in particular—and all of the harms that come with those practices. Problematically, this classification makes biogas eligible for various government programs that also go to truly renewable technologies like wind and solar. And because biogas can be sold into the gas market, it also creates a robust revenue stream for industries like agriculture, oil and gas, and utilities.

What policies and incentives are enabling the expansion of digesters?

Investment into biodigesters is supported by a complex “layer cake of federal subsidies.” In other words, there exists a wide range of state and federal programs that incentivize companies to invest in and install anaerobic digesters. Two particularly prominent examples of this come to mind: California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) and the federal Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). While both programs have meaningful benefits for climate, they miss the mark when it comes to factory farm biogas. The IRA, for example, has provided and will continue to provide, millions of dollars of direct subsidies to biogas operations. It’s also a tax bill, and will accordingly provide massive tax breaks to corporate entities that want to invest in biogas operations, often in connection with large-scale dairy projects.

For example, Farm Forward obtained federal data showing millions of dollars in grants were distributed by one USDA program in 2023 alone to digesters, many of them for dairy operations, representing a significant increase from previous years. What’s more, an analysis of the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy revealed that digesters received some of the most lucrative payments relative to other initiatives. And importantly, these subsidies are more often than not going to large-scale operations.

The LCFS is another unfortunate case of a well-intentioned program that may support the unsustainable expansion and entrenchment of CAFOs. It sets up a system that assigns credits to lower-carbon fuels, including biogas. Credits generated from these operations can be sold into a market of “lower carbon fuels.” According to an analysis of a particular digester operation by the nonprofit Food and Water Watch, “more than 90 percent of the digester’s revenue came from selling government-endorsed environmental credits,” which totaled around $1.9 million.

This would indicate that the LCFS incentivizes large-scale industrial agriculture by opening up new and lucrative revenue schemes. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the push for biogas in the LCFS is rife with methodological concerns and industry influence.

And yes, that industry influence includes meat companies like Smithfield.

What is happening in surrounding communities where dairies and methane digesters are located?

Anaerobic digesters don’t actually mitigate much of the associated pollution that we know comes from factory farms, even if they can reduce some of the methane. Installing one on a dairy operation won’t magically stop the pollution of waterways or airways, for example. In fact, due to the creation of lucrative new revenue streams for industry actors, factory farming is liable to entrench and expand, making it harder to address these harms, not easier. And industrial dairies can produce thousands and thousands of pounds of manure every single day, which inflicts environmental harm on surrounding communities. Anaerobic digesters do not reduce the amount of waste produced by these operations. And government incentives for anaerobic digesters—where manure is viewed essentially as a fuel source—are not likely to encourage reducing it.

And then there’s the fact that the biogas itself isn’t clean—it still has to be burned, which emits toxic pollutants like harmful particulate matter. Not to mention the necessity for more diesel trucks to carry manure, and the building of new natural gas infrastructure (pipelines) to integrate biogas into the broader grid.

Let’s summarize some key points here–why should the expansion of biogas digesters concern us?

The most straightforward reason to be concerned is this: biogas is a boon for factory farming and doesn’t address its fundamental problems. It establishes infrastructure—including new pipelines that are intended to last for decades and it opens significant new revenue streams for industrial dairy, chicken, and pork. In many cases, it may lead to the expansion of herds. But it’s virtually undeniable that it leads to the entrenchment of an industry whose reputation is struggling, and which has gone to great lengths to undermine more sustainable alternatives. I’d bet that most people don’t want more CAFOs in their community, more pipelines in their community, and more handouts to meat companies and oil and gas companies that already get propped up by government programs and political lobbying.

As of 2024, at best, factory farm biogas is a false solution to a very real problem (human-caused methane emissions) that may be abandoned when its fragility and precarity are realized. And at worst, it’s a cynical greenwashing attempt by the industry. They claim to meaningfully reduce emissions while actually entrenching and expanding harmful practices. Sadly, this approach risks institutionalizing these methods long-term and perpetuating all the problems inherent in dairy factory farming.

However, there are promising ways to reduce methane emissions that don’t involve biogas.

What are more effective ways to address farm emissions?

Our emphasis should be placed on supporting truly sustainable agricultural practices and renewable energy solutions that do not perpetuate the harms associated with factory farming. There are better and cleaner ways to mitigate methane emissions that don’t incentivize CAFO expansion and entrenchment like reducing herd sizes and moving to pasture-based systems with cleaner manure management, for example. Reducing the actual amount of waste produced is more sensible than incentivizing more production of it.

We should also push for policies like the Farm Systems Reform Act (and similar legislation) that move us away from the massive, industrialized animal farming system and incentivize higher welfare and plant-based farming. Anyone can look into what kinds of food system reforms are being proposed in their state and look for opportunities to participate. For example, in my home state of Michigan, you have groups like Michiganders for a Just Farming System—a coalition of stakeholders who are working to “address factory farming and the harmful impacts it has on small family farmers, communities, farm animals, the climate, and the natural resources of Michigan.”

Please offer any concluding thoughts.

This all sounds complex, but in some ways it’s relatively simple: An industry that has created and exacerbated a problem is touting a doubtful claim: that the problem is also the key to the solution. And, what’s more, that part of the solution requires that they receive millions and millions of dollars from both public and private investment to expand and entrench operations.

We can avoid this expense and pursue inherently cleaner, simpler ways of reducing methane emissions. While biogas can have benefits in a vacuum, i.e., methane reduction, the right analysis of biogas is one that accounts for how it actually manifests in the food system. Investment in a better food system means investment in better choices, from the federal level to company policy, all the way to consumers. We can start by acknowledging that digesters are not the answer to farm-generated methane–and that the technologies we need must reduce, and ultimately make rare, our reliance on industrial dairy.

Learn more about the impacts of industrial dairy and how to promote more sustainable food practices in your community.